Introducing Refik Anadol and Latent History

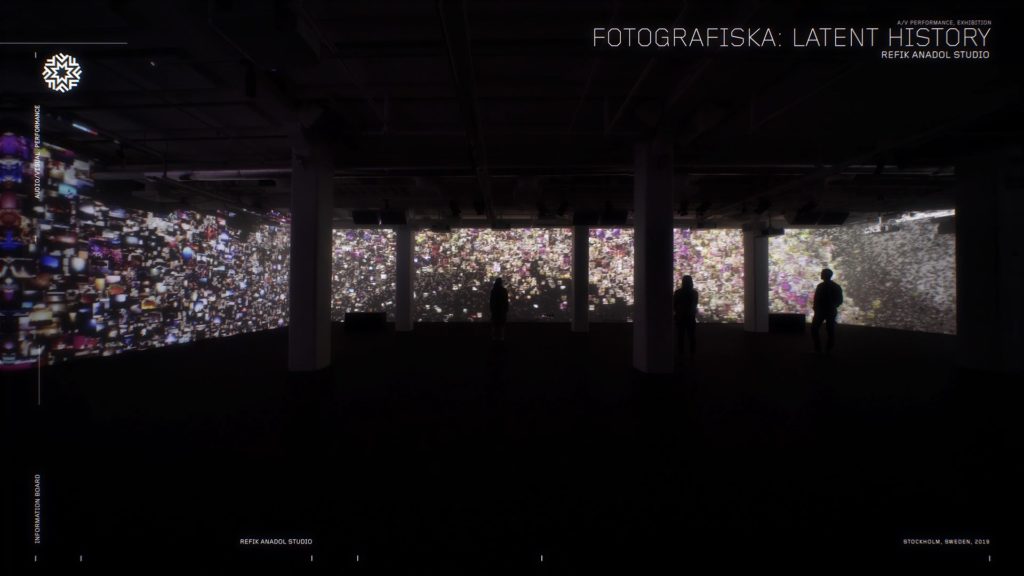

Refik Anadol is a media artist and director born in Istanbul, Turkey in 1985. His media installation ”Latent History” was exhibited at Fotografiska in Stockholm earlier this summer. Latent History takes the viewer on a journey through a beautiful and immersive experience projected on a 55 metre-wide by 3.5 metre-high screen in Fotografiska’s large exhibition hall. It’s a never-before-seen portrayal of Stockholm, as envisioned by machines, using algorithms revealing an alternate history found in archives and old photographs stretching back 150 years. You can get a sense of the experience by watching the video below (made by Refik Anadol and published with his permission).

As the images were drawn from K-samsök/Swedish Open Cultural Heritage I contacted Refik to interview him about his art, how it is created, and how and why he used K-samsök as a source. Note that the interview has been condensed for brevity and Refik’s answers are not quoted verbatim unless explicitly stated.

My interview with Refik

Why did you become an artist? And why did you choose to work with digital art?

Refik tells me he thinks a major reason for his interest in becoming an artist was watching Blade Runner when he was eight years old. The images of a future and futuristic city sparked his imagination. His mom later gave him his first computer, a Commodore 128, and he believes it, and Blade Runner, may be why he chose to do digital art. His focus as an artist is on urban spaces, futurist spaces, and to use computation, data and light to imagine, and make the invisible visible.

In regards to Latent History specifically – can you tell us a little bit about that artwork and how it came about? Why Stockholm, why machine learning and computer vision, and why use, in parts, archival imagery as a basis for your own work?

Three years ago Refik had the opportunity to be an Artist in Residence at Google Arts & Culture. It was there that he first started working with machine learning and AI and realised its potential. During his residency he created a projection experience onto to the LA Phil’s Walt Disney Concert Hall (you can get a sense of that experience here, and learn more how it was made here). Since then he has continued to explore the potential of machine learning and AI as tools to support the creation of media art experiences. He’s begun to ask the question: can machines dream?*

Fotografiska in Stockholm were also interested in exploring AI and AI-generated imagery and invited Refik to create an experience for exhibition at their venue. One of the reasons Refik chose to work with archival imagery for his Latent History experience at Fotografiska was to explore memory, collective memories and urban space. He also wanted the experience to feel like ”Infinite Cinema”.

*Taking us back to Blade Runner: the book the film is based on is Philip K. Dick’s ”Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?”.

How did you learn about Stockholmskällan, K-samsök and Europeana? How did you select which imagery to choose from them? How many images from them did you use in the end? Did you just sign up for an API-key just like any other third party developer?

When Refik and his team were invited to create something for Fotografiska they began to research what sources of historical imagery are available for Stockholm. That was when he learned of Stockholmskällan, K-samsök/SOCH, and Europeana. For K-samsök and Europeana his team just applied for/signed up for API-keys and started to work with the imagery. Stockholmskällan they had to scrape. Latent History used about 23 000 images of Stockholm, most of them drawn from K-samsök and Europeana. As they wanted to focus on Stockholm as an urban space, its form and architecture, they tried to select imagery where there were few are humans shown. They also made sure to select a few images of Stockholm at sunrise and sunset, to give a sense of the passage of time.

For archives, museums and libraries who would like to see their collections used in artistic works – what would be your advice to them in order for that to happen more often?

The first thing Refik mentions is for libraries, archives and museums to offer (user-)friendly APIs and easy access to data. Easy to sign up for, returning images that are free to reuse for artistic purposes.

The second is to offer residencies to artists. Invite them to come and work at your institution, together with your employees, and with your collections. Refik values his residency at Google Art & Culture very highly and believes it’s a good format that others can follow.

The third is related to the first and second: beyond having an API or otherwise releasing your content for reuse invite artists to co-creation workshops, with the collections experts of your institution. The more an artist understands what is in the collection, the more they can do with it:”knowledge is [an artist’s] pigment”.

In this context Refik also mentions the challenge of learning just what is available in a large archive. How do you know what is there? No search bar can tell you and he thinks artworks, or other visualisations, can help artists better understand what’s in a collection and make using its contents to create new works easier. The underlying design metaphor for large archives needs to ”go beyond shelf design”, beyond a direct translation of the analogue to digital.

Digital art has been around for a while, almost as long as there has been computers! How do you see it changing in the coming years?

Here Refik answers that in the coming 5 years or so he thinks we will see radically improved algorithms, especially in regards to GANs (Generative Adversarial Networks). This is an area in rapid development already. He also thinks we’ll see new hardware that makes it possible to crunch ever increasing amounts of images e.g. graphic cards specialised for machine learning/AI and even quantum computing.

Together that should allow AIs/machines to delve deeper into ever larger collections of images and increase the verisimilitude of the virtual architectural space and allow us to “fly inside the mind of a machine“.

Dear friends, I’m very excited to share our studio’s next exhibition “Latent History“ opening @fotografiska in Stockholm! For this project we were able to narrate around 1 million photographic dataset of archival precious materials with machine intelligence. pic.twitter.com/k6i8s84PkG

— Refik Anadol (@refikanadol) June 28, 2019

More about Refik Anadol

Refik Anadol is a media artist and director born in Istanbul, Turkey in 1985. Currently he lives and works in Los Angeles. He is a lecturer and visiting researcher in UCLA’s Department of Design Media Arts. He works in the fields of site-specific public art with parametric data sculpture approach and live audio/visual performance with immersive installation approach, particularly his works explore the space among digital and physical entities by creating a hybrid relationship between architecture and media arts with machine intelligence. He holds a Master of Fine Arts degree from the University of California, Los Angeles in Media Arts, a Master of Fine Arts degree from Istanbul Bilgi University in Visual Communication Design, as well as a Bachelors of Arts degree with summa cum laude in Photography and Video.